Interview By – Chahat Sharma

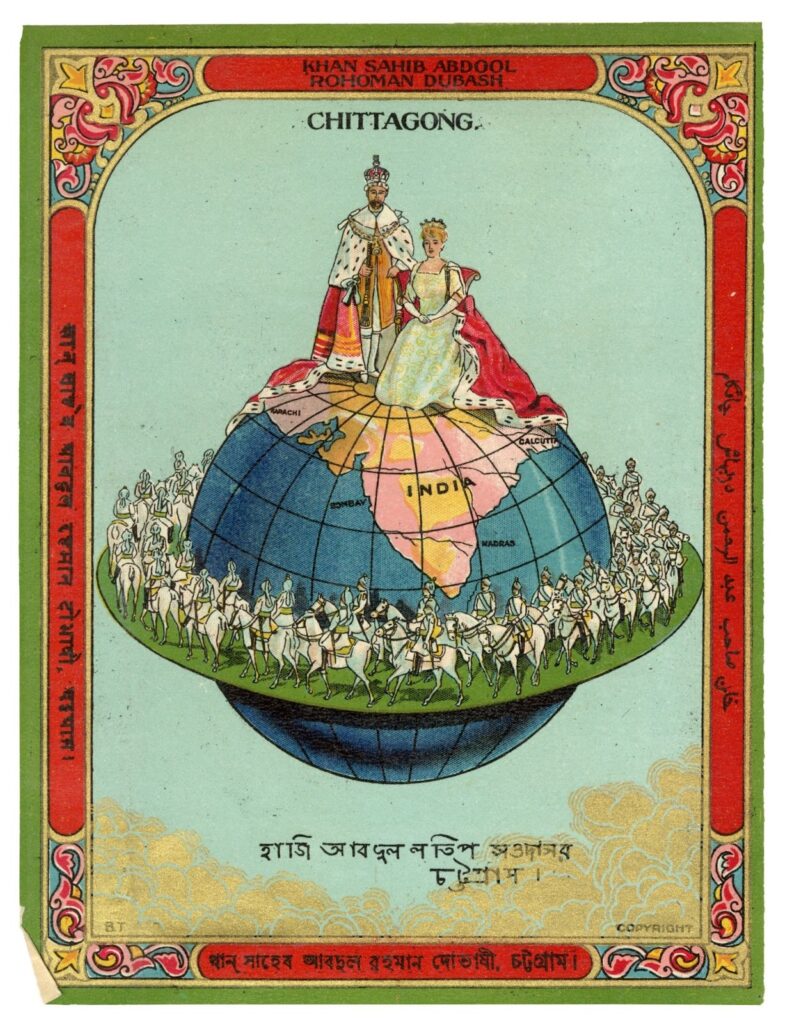

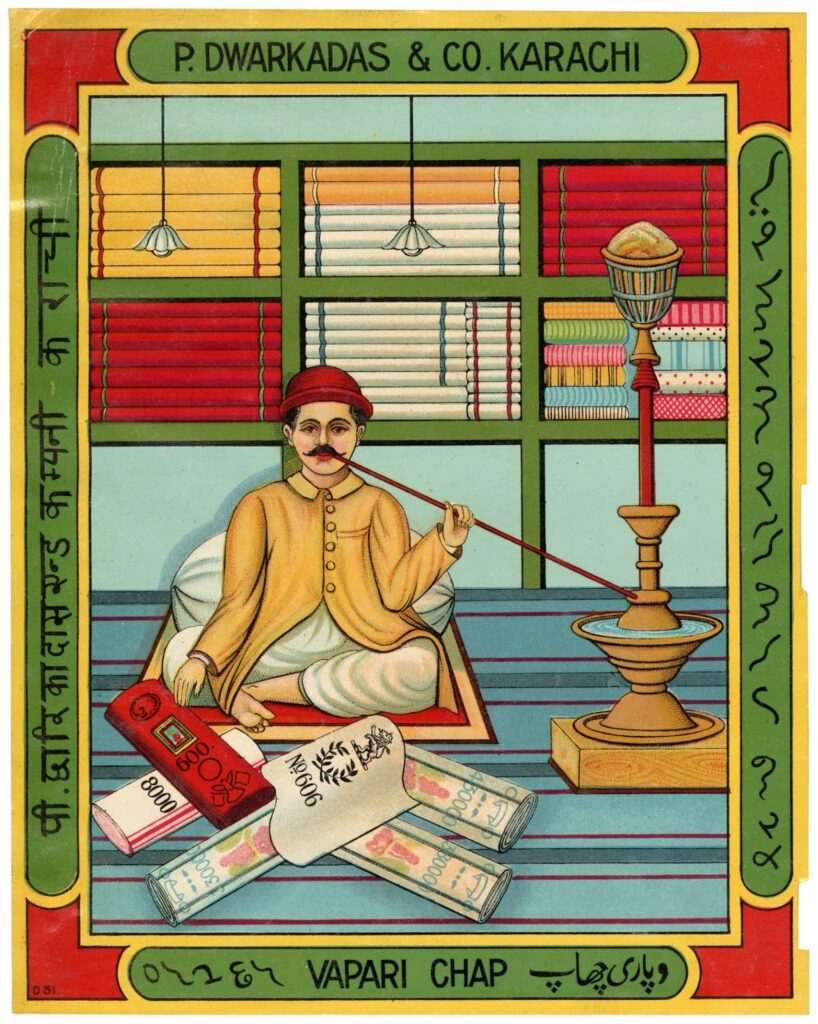

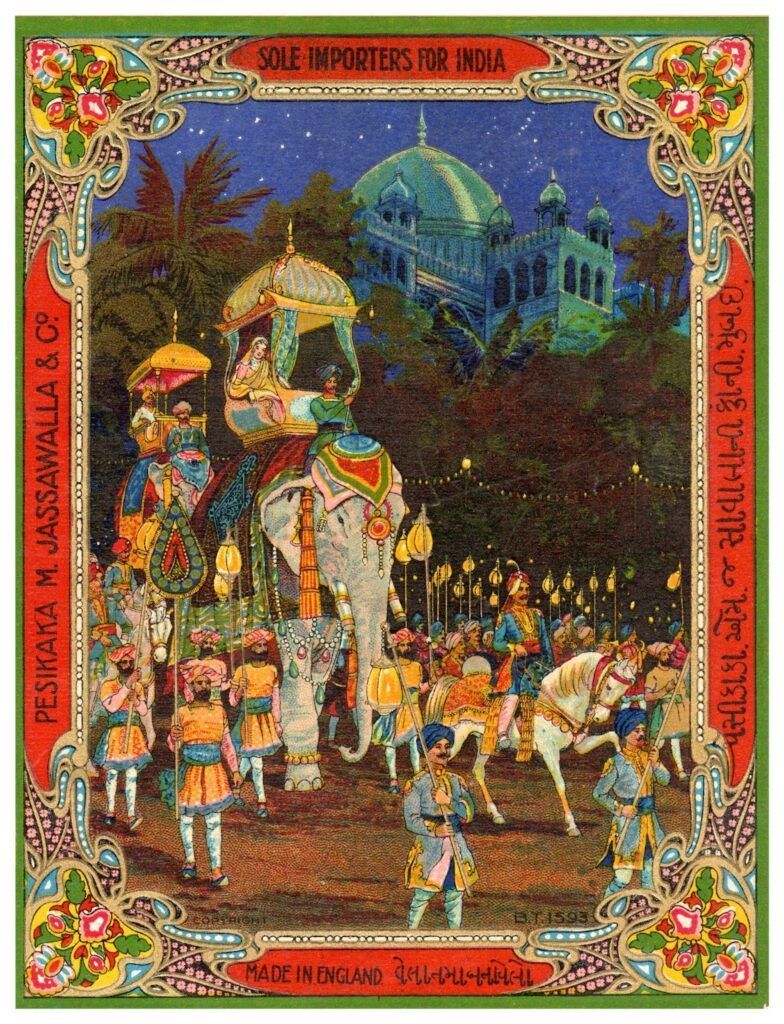

In the bustling bazaars of late 19th and early 20th century India, colour was commerce and imagery was persuasion. Long before logos and billboards dominated the landscape, textile tickets, known variously as tika, chaap, or shippers’ marks acted as the earliest forms of mass visual branding. These chromolithographed paper labels, affixed to bales of mill-made cloth arriving from Manchester or Mumbai. They were not mere packaging, they were cultural messengers: bearing gods and monarchs, landscapes and fantasies, nationalist symbols and foreign aspirations.

Ticket Tika Chaap: The Art of the Trademark in the Indo-British Textile Trade, at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, brings nearly 300 such labels into conversation with history, design, technology, and identity. It reframes these overlooked fragments of commerce as artefacts of artistry, aspiration, and collective imagination.

To understand the curatorial process behind this ambitious exhibition, ACF spoke to Shrey Maurya, co-curator of Ticket Tika Chaap alongside Nathaniel Gaskell, and currently Research Director at MAP Academy. In this interview, Maurya reflects on the labels’ unexpected sophistication, the mysteries of artistic exchange that shaped them, and how small scraps of paper once travelled from cloth registers to living rooms, altars, and memory.

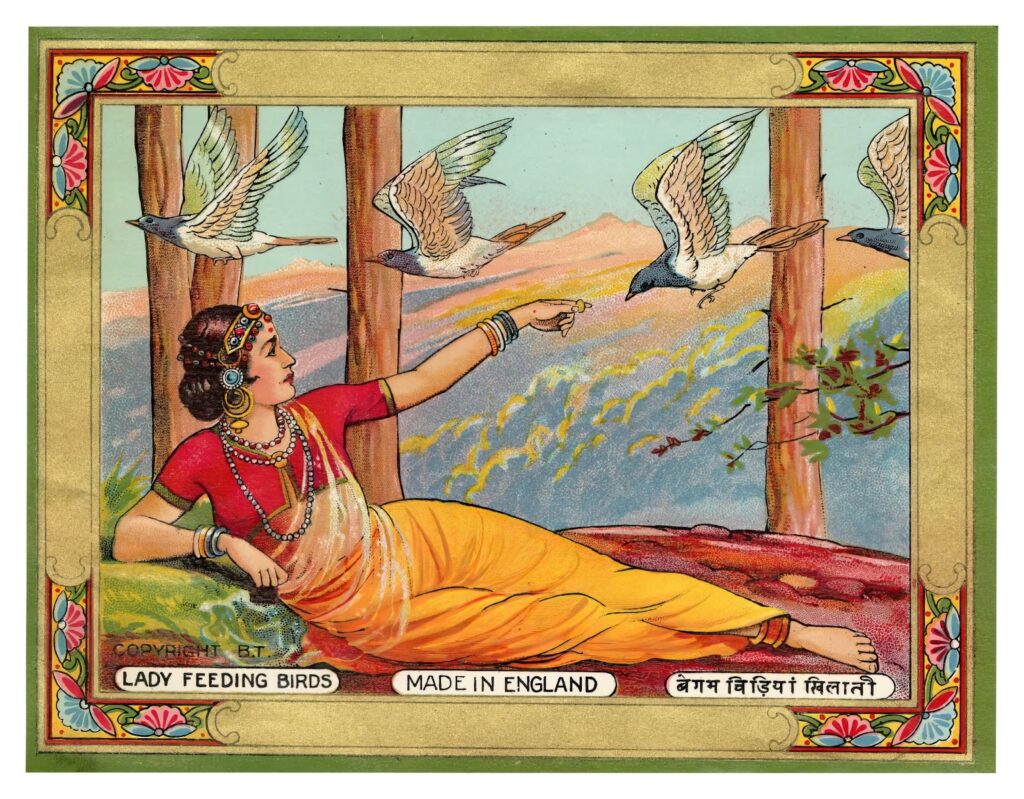

© Textile Label, Late 19th – early 20th Century, Chromolithography (POP.03415)

1. What first drew you to textile tickets as the subject of an exhibition, given that they are often treated as commercial leftovers rather than cultural artefacts?

As curators, Nathaniel Gaskell and I were fascinated by the visual quality of the labels, their bright colours, their intriguing designs, as well as the sheer volume and variety. The Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru (MAP), alone has around 7,000 such labels and related ephemera. As we studied this collection, we realised they were more than commercial objects. These labels were among the earliest coloured print advertisements circulating in India from the late 19th century onwards. They vividly reflect the global boom in consumerism, industrialisation, advertising, printing, and popular art. They were also curated objects in their own right, with great attention paid to their central image. Moreover, textile labels emerged from the combined labour of several skilled yet anonymous artists and technicians. All of this gave them a unique status as cultural artefacts.

2. Out of the 300 pieces featured in the exhibition, did any unexpected finds shape its direction?

One of our key research strands was understanding the visual inspirations behind textile labels. As we studied MAP’s collection more closely, we discovered fascinating examples of image circulation. While we know agents of merchant companies sent sketches or prints from India to printers in Manchester, some visual similarities were harder to explain. One textile label nearly replicates a folio from the Kanchana Chitra Ramayana, an illustrated manuscript with limited readership. How such imagery resurfaced decades later remains a mystery.

We also found labels echoing works by the American artist Maxfield Parrish, and one clearly modelled after an illustration from The Garden of Kama. In each case, designers adapted the imagery, adding Indian costumes or inserting Krishna to suit local tastes. We chose to display such pairs in a dedicated section, though similar echoes surface throughout the exhibition.

© Textile Label, Late 19th – early 20th Century, Chromolithography (POP.03464)

3. These labels once circulated in bustling bazaars and cloth markets. How did you think about retaining that atmosphere when translating them into a museum setting?

The labels are mostly mounted onto folios of archival registers, which was a spatial limitation. However, we opened the exhibition with cloth samples still bearing labels to evoke how textiles were originally displayed. We also created an immersive room covered with hundreds of labels and folios, allowing visitors to experience the sheer visual density of the bazaar. This space is further animated by a short film by filmmaker Amit Dutta, which uses textile labels to narrate a story of trade and geography, alongside a tactile archival register.

4. Many tickets combine Indian deities, European monarchs, and global symbols. What do these visual choices reveal about colonial trade, aspiration, and consumer identity?

The very product these labels promoted, mill-made cotton goods, reflected a seismic 19th-century shift: India went from leading global textile production to becoming the largest market for British manufactured textiles. Labels reveal what merchant agencies believed would appeal to Indian buyers. Royal portraits, British or Indian connoted quality. Deities and holy sites signalled auspiciousness. Independence-themed imagery evoked Swadeshi sentiment. Yet these labels did not invent such symbolism, they borrowed from a thriving bazaar visual culture of chromolithographs, popular prints, and new media.

5. Textile labels were both advertisements and unofficial trademarks. How do you see them fitting into the early history of branding and visual persuasion in India?

Textile labels were intensely visual tools, drawing from both traditional and modern imagery to persuade buyers, much like contemporary advertising. The image helped establish a recognisable trademark and acted as a mnemonic for buyers. Many labels featured titles with words like chaap or ticket, which customers could use to reference a brand. Even without text, a powerful image could secure recall. Labels often incorporated merchant or mill names in English and regional languages, embedding brand identity into visual form.

© Textile Label, Late 19th – early 20th Century, Chromolithography (POP.06060)

6. Some of these tickets ended up on walls, in trunks, even on altars. How do you interpret their transformation from packaging to personal artefacts?

This reflects a world where images had become widely accessible commodities, thanks to advances in mass printing, posters, postcards, photographs, wrappers, magazines. Scholars have observed how popular print culture democratized worship by allowing people from all backgrounds to bring images of deities into their homes. The reuse of textile labels represents personal curation, a familiar instinct even today when we ‘save’ images that resonate with us.

7. Chromolithography changed how images were produced and circulated in colonial India. How did this technology shape the look and impact of these tickets?

The impact is most visible in the use of colour and scale. Textile labels could feature 13–14 colours, requiring complex design breakdowns for printing. Chromolithography—via stone and metal plates was ideal for this. Labels were typically printed in sets of a thousand. Given India’s vast textile market, hundreds of thousands were likely produced, achievable only due to mechanised chromolithography.

8. What strategies did you use to make small, everyday objects feel significant in a gallery space without losing their context or intimacy?

We framed the exhibition around the processes and motivations behind label design and production, going beyond categorising them as everyday ephemera. Labels were commercial, but they were also communication devices, a message from merchant to buyer. Our display themes evoke this conversational quality, encouraging viewers to ask why certain images were favoured, and how visual persuasion worked then versus now.

9. Did gaps in archival records, such as missing artists or undocumented manufacturers, challenge your curatorial process?

Absolutely. One major gap is the role of the artist. While MAP has records from a Manchester-based printing firm, B. Taylor & Co., which shed light on the business side, the creative process, how artists sourced and adapted imagery, remains opaque. Similarly, documentation of Indian textile label production, such as at the Ravi Varma Press or firms in Mumbai and Ahmedabad, is limited.

10. Looking at modern branding today, what resonances or contrasts do you see with these historical labels?

The biggest contrast lies in the medium. Paper labels still exist, but they lack the spectacle of historical ones. However, the emotional triggers remain unchanged. Celebrity endorsement, humour, romance, aspiration, whether in a 1900s label or a 2025 billboard, the psychology of persuasion is remarkably consistent.

© Textile Label, Late 19th – early 20th Century, Chromolithography (POP.04196)

Ticket Tika Chaap is more than a history of labels, it is a study of how images travel, persuade, and endure. What once clung to bolts of cloth now commands the walls of a museum, not by nostalgia but by sheer visual intelligence.

If you are ever fascinated by how design shapes desire, or how commerce becomes culture, then this exhibition is essential viewing.Visit MAP Bengaluru between March 22nd and November 2nd, 2025, and step into the archive of imagination that once clothed a nation.