© Philippe Calia

Interview by: Chahat Sharma

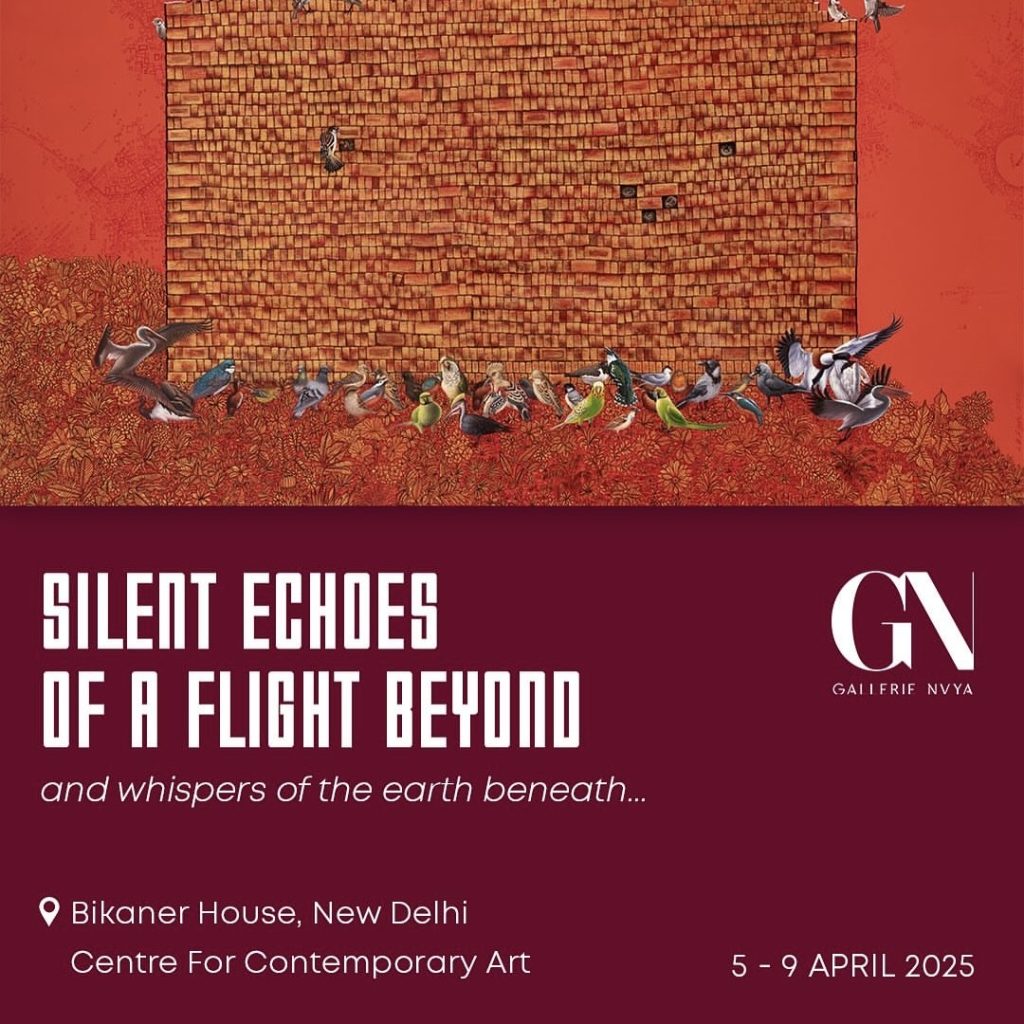

This interview, conducted on behalf of ACF, explores In Celestial Company, an exhibition at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, curated by Priya Chauhan. Rather than placing divinities at the centre, this show turns its gaze toward those who have long stood beside them, the carriers, companions, and celestial collaborators who make divine action possible. From Garuda and Nandi to Kinnars, Ganas, angels, flag-bearers and hybrid beings across cultures, Chauhan presents a radical reframing of mythology, one that foregrounds interdependence, symbolism, and the ecosystem of the sacred.

What does it mean to focus not on gods, but on those who carry them? What happens when marginal figures step into the spotlight? In this conversation, Chauhan unpacks the philosophical, visual, and emotional provocations that drive the exhibition, while also touching on representation, technology, hybridity, and the transformative power of mythic beings.

© Philippe Calia

1. What was the initial spark or inspiration behind centering an exhibition on celestial companions rather than the deities themselves?

I have always been drawn to the things that sit in plain sight but rarely get a closer look. The idea of In Celestial Company grew from this urge to shift the gaze. Much like in our Ram Kumar exhibition, where the other facets of the artist’s personality got to shine in a different light, here too, we thought: what if we started with the margins instead of the center, start with companions, who get space all around the central figures, instead of the deities? What new stories might surface if we explored the ecosystem around the divine, the margins of its visual imagery?

2. With over 100,000 artefacts in MAP’s collection, how did you approach the process of selecting works that best represent these mythic beings and their narratives?

We began with themes that felt urgent, our broad bifurcation being beings who carry and accompany. Then we looked at gaps: in representation, in how our gaze is often shaped, how we tend to blur out certain figures. Within the logistical limits of display and conservation, we worked to create a range in material, form, context, and time. The final selection reflects that balancing act.

3. Well-known figures like Garuda and Nandi appear alongside lesser-known beings such as Kinnars, Ganas, and Dhumavati’s crow. How did you balance familiarity and discovery in your curatorial choices?

This was done very consciously! For every familiar companion, we wanted a lesser-known, often overlooked being to sit in the same space. So Garuda might lead you into the story, but it is the crow of Dhumavati, a figure of inauspiciousness and darkness, who invites deeper reflection. It was important that even those figures usually shrouded in shadow were seen in the light, on equal footing, highlighting how everything works in this balance throughout the universe, even beyond this mythological context.

© Philippe Calia

4. The exhibition features objects across cultures and time periods, including colonial-era pieces and angelic figures. How do cross-cultural influences shape the narrative of the show?

Cross-cultural presence was always a part of our storytelling. Mythic companions aren’t unique to one tradition, they appear in Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, Islam. One of the earliest works in the exhibition is an image of Angel Gabriel, who is Jibril in Islam. That it was once misidentified as Garuda and reidentified as Angel Gabriel, also Jibril, shows just how fluid and shared our iconographies are. These overlaps aren’t just artistic; they reflect the porousness of belief and exchange.

5. Many of these beings have traditionally existed in the margins of mythology and iconography. What does it mean to bring them to the center of the visual narrative today?

It is a reminder that nothing works in silos, not even the divine. These beings, often on the edges of stories or frames, are in fact the enablers of action, the ones who hold the scene together. In shifting the spotlight onto them, we are also reflecting on broader ideas of interdependence and how the margins are often centered in themselves. That is true in mythology, and in life.

© Gandharva, Late 19th century – early 20th century, Wood (SCU.01885)

6. Can you share a specific artwork or artefact from the exhibition that surprised you during the research or curation phase? What makes it stand out?

One set that really stood out to me were the flag-bearer figures from Pondicherry, exquisitely hybrid in nature. At first glance, they appear quite anglicised, but a closer look reveals classical iconographic imagery of Murugan or Kartikeya with consorts on their vahana peacock or Paravani on the gilded fan. There are also angel-like wooden hanging sculptures on display with similar, very mixed, stylistic features. These objects embody a stunning fluidity, they are not just cross-cultural, they are reciprocal. Likely created in a space where colonial Christian and Tamil Shaivite audiences intersected, they show how forms travelled, merged, and were revived in new visual languages. They may have existed in sites of shared worship or ritual, resonating with multiple faiths at once. That sense of permeability, where iconography bends but spirit holds, was both moving and revelatory.

7. The 360-degree storytelling booth on Garuda adds a multimedia dimension. What role does technology play in reimagining mythic narratives for contemporary audiences?

Technology allows us to make these stories more alive, more embodied. Not everyone connects through the same ways and mediums, some want to hear, see, feel. The 360-degree experience on Garuda was a way for us to stretch our creative muscle, but also to make space for diverse modes of engagement, as for some, mythology comes alive through sound and motion. And for younger visitors especially, that’s often the entry point.

© Navneeth Dinesh

8. In Indian visual tradition, animals and hybrid beings often carry deep symbolic meaning. What recurring themes or symbols did you notice while curating these varied depictions?

One strong theme was transformation, how a trait often seen as vice-like or negative becomes powerfully symbolic. The mouse, once a demon, becomes the divine vehicle of Ganesha. The crow, feared in some contexts, becomes a loyal companion to Dhumavati. These beings remind us that meaning is always fluid. That what feels marginal, small, or even chaotic has value. It is a lesson in empathy, really. And there is another layer to it, that of companionship. How things work together, how relationships often support and supplement. The layers here are manifold, really.

9. Has working with this theme shifted your own understanding of these beings or their role in visual culture? If so, how?

It has made me see balance differently, and think about dependence in a new way. The divine does not stand alone. And in the visuals, you begin to notice how every little detail, every mount, every creature is part of a larger ecosystem. These beings aren’t just accessories, they are anchors. They make the story possible. There is no story without them.

10. From a curator’s perspective, what do you hope visitors — especially younger or first-time museum-goers — take away from meeting these mythic figures?

I hope they walk away with questions. I hope they look at the “main character” but also at who is standing beside them. And I hope they see the power of stories, how myths evolve, how symbols shift, how even a small creature can carry cosmic weight. Most of all, I want them to feel wonder. That is where everything begins.

© Navneeth Dinesh

In In Celestial Company, mythology is not retold, it is reoriented. By turning toward the companions rather than the crowned, Priya Chauhan invites us to rethink power, presence, and the stories we overlook. These beings — mouse, crow, angel, peacock, elephant, hybrid, halo-bearer are no longer silent attendants. They are protagonists.

Step into their world, and perhaps, reimagine your own.

Venue: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), 22 Kasturba Road, Bengaluru

Dates: September 13, 2025 – February 15, 2026

Timings: As per museum hours