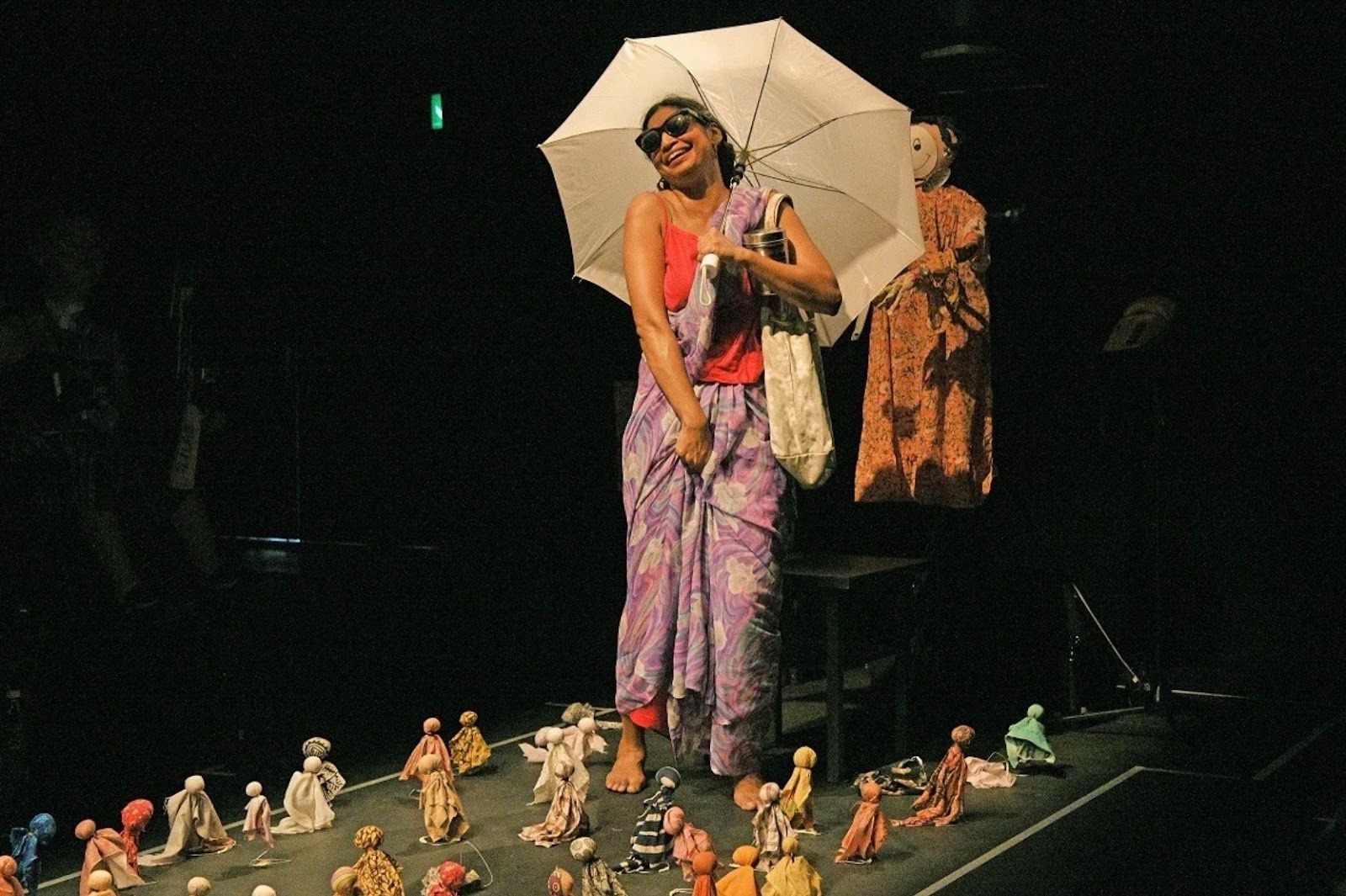

Hailed as one of the foremost voices of Hindustani classical music today, Kaushiki Chakraborty belongs to the illustrious Patiala gharana and continues to carry its legacy with remarkable grace. Yet, her artistry extends far beyond tradition. Through her khayal gayaki, thumris, and semi-classical repertoire, Chakraborty has become an impassioned storyteller, reviving forgotten voices of women performers who shaped the cultural fabric of India but were long denied their rightful place in history. In this conversation with journalist and writer Abhilasha Ojha, Chakraborty reflects on her ongoing 12-city tour, her latest project Pankh, a six-song album and an interview series with music director Shantanu Moitra, and her deep engagement with the stories and struggles of women musicians. Together, Ojha and Chakraborty unravel not just music but the legacy, research, and personal journey that tells the audience about her practice.

Ques. Why is it essential for you to study women artists in your performances?

You are thoroughly investigating thumris, the musicians behind the thumris, almost doubling up as a musicologist yourself.

Kaushiki Chakraborty: Though I have always remained enamoured and attracted towards the form of thumris, it was during COVID when I thought of researching thoroughly about the many women artistes who have given their voice to the numerous thumris that we sing today. I think, at one point, there were specific questions on my mind related to the genre. We all sing these beautiful compositions, we listen to them, but we do not know much about the women who have sung them. We take so much pride in singing these compositions, but rarely do we find the names of the composers, many of whom have been women who have been lost in the pages of history. We have names of male composers in bandishes, but rarely names of women composers. Why is that? It is because society gave them no regard or respect. No acknowledgement was ever given to them.

Ques. How did you go about researching thumri singers?

Kaushiki Chakraborty: As part of the Indian classical music tradition, many composers would put their name and identity in their compositions. Today, hundreds of years later, we still sing their compositions. But I have not found many of the women’s pen names in compositions, barring a few. My research started with the intent of paying respect to the female composers and singers – if I wanted to research even Gauhar Jaan, for instance, who is still quite well known, I do not know where to go! I spoke to Vikram Sampat, the author of Gauhar Jaan’s biography, and even he said that apart from some electricity bills and some unpaid taxes, there is nothing. I was reading a lot of books, and I even visited Benaras and spent time with the families of many of these incredible women performers. Where is the legacy of these immensely talented women who have contributed so much to Hindustani classical music? Where can we go and offer tributes to these great artists? Nowhere.

Ques. What are some of the stories that you came across in the course of your research on these women artists?

Kaushiki Chakraborty: Well, look around you, do you find auditoria or festivals in the names of female artistes? They are missing. For the longest time, radio was not recording women from a certain strata of society simply because they were singing in kothas. None of their background made them lesser artists, but their significance has been diminished for the longest time in the larger picture. Many left singing despite being immensely talented and went on to pursue other professions. The stories of many of these women drowning their instruments in the river Ganga are horrific and still send shivers down my spine.

Ques. As a singer and as a woman, how does this marginalisation make you feel

Kaushiki Chakraborty: I have been awestruck by the voices of so many thumri singers and each time I sing classical music on the stage, I am aware of my father’s legacy that I carry but as a human being, each time I sing thumris or any of the compositions sung by women singers, I am equally aware that I am also carrying their legacy. They are performers who were among the first ones to come and be on a par with their male counterparts and perform in front of an audience with such pride and honour. Ye raasta unhone banaya hai mere liye (they have paved the way for me), so I owe the tribute to them as a girl, as a woman, as an artist, as a fan girl, as a student. It is a reason why my music performances allow for engagement with these compositions and give people an understanding of these female performers.

Ques. Much of the way children think is shaped by family. How was your childhood, especially since you were born in a musical family?

Kaushiki Chakraborty: I was never raised as a girl; I was raised as a human being. I was never told that I had to limit myself as a girl. I was 11 years old when I travelled alone, took a flight from Kolkata to Bangalore to sing. My mother said, ‘You are going out of the home to perform, and you are taking the pride, honour, respect of the family, and you have to maintain it and enhance it, and you come back home.’ I was raised like a warrior. I was trained to become a performer and singer, with the knowledge that it was my divine purpose. My parents have never thought of my gender; they have always considered me to be the person on whom the family’s legacy is run, which is why, once I’m on stage, I’m a spokesperson for my art form.

Apart from that, there was emphasis on daily riyaaz, and I was always careful about what I ate. I have never tasted ice cream or puchka in my life.

Ques. Where’s the strength coming from to do everything – be a wife, a mother, a daughter, a sister, and a classical musician?

Kaushiki Chakraborty: I have great support from my husband and my son, and we are best friends; my child is also someone who understands that his mother is a performing artist. What is helping me is the mutual respect and trust between family members. The reason why I am devoted to my music is that my entire ecosystem of family is helping me shine. I am indebted to them for driving me. Because of their trust and love, I can do so much. I cannot even imagine the plight of women artists who did not have this sort of support.

Through her music, Kaushiki Chakraborty embodies both inheritance and innovation. She carries the weight of history and the glory of her gharana and the silenced voices of forgotten women with a rare sense of responsibility and reverence. Whether on stage or in conversation, she reminds us that Hindustani classical music is not just about ragas and rhythms but also about stories, resilience, and the humanity of those who kept the tradition alive against all odds.

In Pankh, as in her larger journey, Chakraborty invites audiences to listen not just with their ears, but with their hearts.

This interview with Abhilasha Ojha offers a glimpse into her world, capturing the strength, humility, and artistry that make Kaushiki Chakraborty one of the most compelling voices of our time.