By Bhavya Balamurali

Scattered across the worlds grandest museums and darkest vaults are relics of empires, rebellions and ancient faith which were silent witness to conquest, colonial plunder and unresolved legacies.

The Gold Crown of Emperor Tewodros II – Ethiopia

Image Credit: vam.ac.uk

The gold crown of Emperor Tewodros II is one of Ethiopia’s most significant cultural treasures. Once a symbol of imperial authority and spiritual devotion, the gold crown carries with it a story of ambition, loss and contested legacy.

Believed to have been commissioned in the 18th century by a local ruler and her son, it was later housed in the Church of Our Lady of Qwesqwam in northern Gondar, which eventually came into the possession of Emperor Tewodros II, a powerful and ambitious monarch who sought to unify Ethiopia’s fractured region. Known for both his grace and ferocity, Tewodros assembled a remarkable collection of religious and royal artifacts at his fortress capital of Maqdala, considered by some historians as Ethiopia’s first national museum.

In 1866, British forces invaded Maqdala, leading to the emperor’s death and the looting of countless treasures, including the gold crown. Today, the relic resides in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, symbolizing both Ethiopian rich imperial history and the enduring scars of colonial plunder.

Many treasures were looted from Maqdala, including crowns, manuscripts and sacred tabloids. Now housed in museums like the British Museum and the V&A. With Ethiopia repeatedly requesting its return and many tabots returned to Ethiopia, as part of reclaiming its cultural heritage.

Rosetta Stone – Egypt

Image Credit: Rosetta Stone, British Museum

No other artifact shaped the understanding of ancient world and history like the Rosetta Stone.

Unearthed in 1799 by French soldiers in the Egyptian port town of Rashid, the hefty 760-kilogram slab was no ordinary relic, it carried a decree issued by King Ptolemy V, carved in 196 BCE. What makes the stone soo extraordinary is its trilingual inscriptions which includes, Hieroglyphs for the Gods, Demotics for the people and Ancient Greek for the rulers. The Greek text offered scholars the missing key to finally crack to the code of the hieroglyphs which was indecipherable for centuries.

After changing hands from the French to the British in 1809’s, following a brief stint with Napoleon’s army, the stone landed in the British Museum in 1802. Today it’s the museums most visited object, much to Egypt’s frustration, who have been tirelessly campaigning for its return, calling it an icon of Egyptian heritage.

Rosetta Stone marks the moment humanity regained the ability to read the voices of ancient Egypt, transforming the silent stone and mysterious symbols into a history we could finally understand.

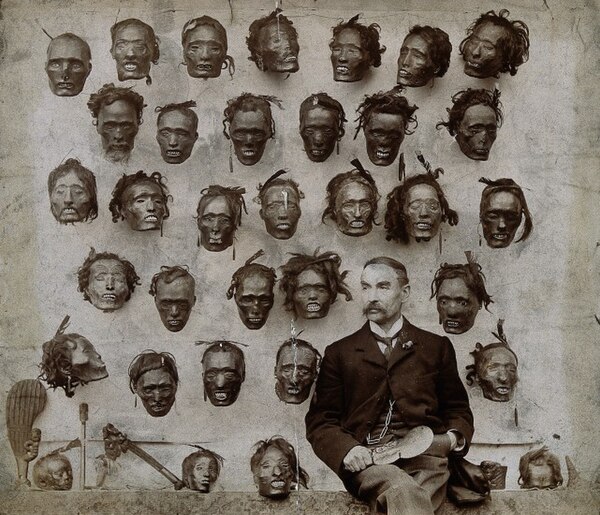

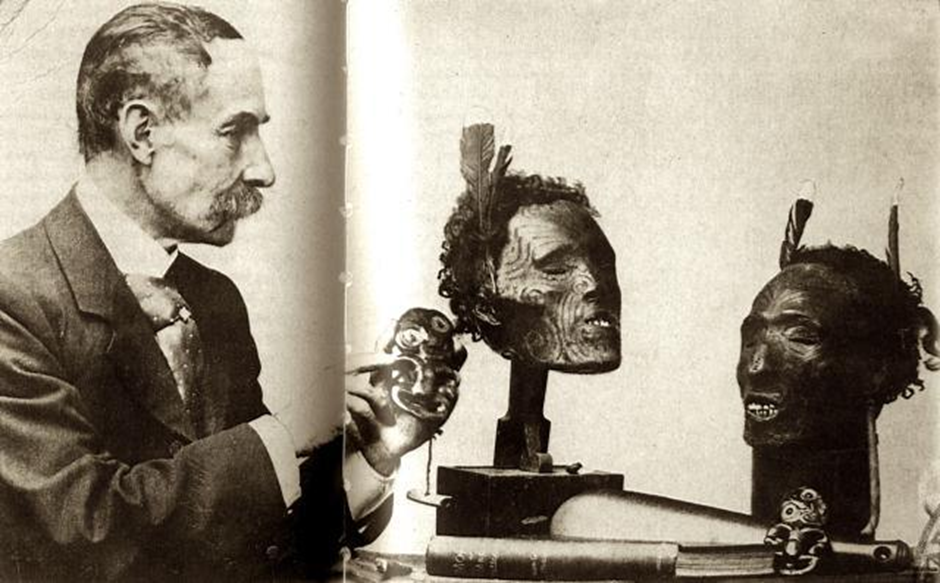

Mokomokai – New Zealand

Image Credit: University of Wellington Library via CVLTURE

In the heart of New York’s American Museum of Natural History lies the most haunting and unusual collection of 30 mokomokai, the preserved, tattooed heads of Māori tribesmen.

Among Māori, intricate facial tattoos, or moko, mark a person’s status and identity, holding deep cultural and spiritual meaning in Māori society. Carefully preserved after death using flax fibers, gum and shark oil, the heads were family heirlooms, brought out during sacred ritual.

Upon the arrival of the British in 19th century, these cultural artifacts became a sought-after curiosity. British officers like Major General Horatio Gordon Robley, fascinated by the artistry and mystique of mokomokai, not only sketched them but also began collecting them. As European demand soared, a grim trade emerged, which turned cultural curiosity into commerce. Robley’s collection was acquired by the American Museum of Natural History in the 1890’s.

Today, these artifacts serve as a powerful witness to Māori tradition and a sobering reminder of colonial-era exploitation, sparking ongoing discussion about rightful ownership and the ethics of displaying human remains in museums.

Tippoo’s Tiger – India

Image Credit: Tippoo’s Tiger, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

One of the most peculiar and captivating objects in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is Tippoo’s Tiger, a wooden automaton with a sharp political bite.

Created for Tipu Sultan, the defiant ruler of Mysore, the fiery life-sized wooden automaton depicts a tiger mauling a European soldier. A striking image of defiance during a time of colonial tension. Ingeniously designed, the tiger imagery houses a mechanical organ, which when turned, produces soldiers agonized screams while making the arm jerk in distress. Tigers were a recurring emblem in Tipu Sultan’s court, weaving them into his weapons, coins and royal insignia.

After his death during the British siege of Seringapatam in 1799, his prized possessions were looted, with Tippoo’s Tiger making its way to London, quickly becoming a public sensation. Today it stands to intrigue visitors, standing as a vivid relic of art and rebellion.

The Parthenon Sculptures – Greece

Image Credit: The Parthenon Sculptures, British Museum

Few artefacts have stirred as much global debate as the Partheon Sculptures. Famously known as the Elgin Marbles, they were created in the 5th century BCE to adorn Athens’s Parthenon, depicting mythical battles, religious ceremonies and legendary gods.

Carved between 447 and 432 BCE for the Parthenon temple atop Athen’s Acropolis, these masterpieces celebrated Athena, the city’s patron goddess. In the early 19th century, Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empires, controversially removed about half of the surviving sculptures, then transported them to Britain a decade later, which were then acquired by the British Museum in 1816.

For Greece, their absence leaves a vital piece of its ancient history and identity behind. The Acropolis Museum, built in 2009, displays casts in the place of the originals. While legal restrictions and diplomatic sensitivities complicate their return, ongoing dialogue and international support for cultural repatriation are shifting attitudes towards cultural ownership and historical accountability. These marbles have become more than relics: they remain the symbol of both ancient artistic brilliance and the complex legacy of colonial-era collecting.

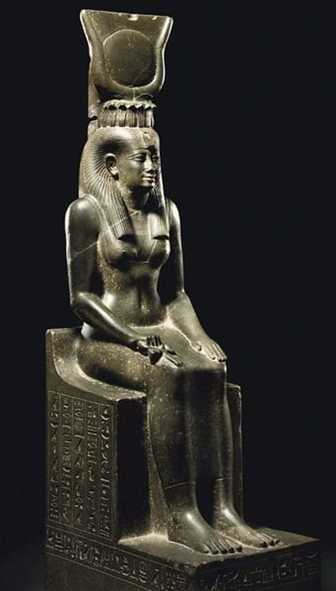

Egyptian Greywacke Isis – Egypt

Image Credit: Isis Healing Statue via isiopolis

Among the most enchanting relics from Ancient Egypt, few artifacts weave together myth, magic and history quite like the Egyptian Greywacke Isis. Dating back to around 664-525 B.C. this elegant statue was carved during the Late Period of Dynasty XXVI, depicting the goddess, Isis.

Isis is seated serenely on a throne, her head crowned with a sun-disc nestled between cow’s horns, believed to be the symbol of protection and divine authority. Legends hold that this is no ordinary sculpture, rather it holds the source of healing. Ancient Egyptian would pour water over the magical inscriptions etched onto the sculpture, collecting it to cure ailments and ward off venomous creatures.

Thought to have stood in a public courtyard or temple, the sculpture was lost in the sand of time, until a French diplomat acquired it in the 1840’s in Alexandria. The artifact journeyed through European collections before being auctioned for nearly $6 million, making it one of the most valuable Egyptian artifacts ever sold.

The Greywacke Isis embodies Egypt’s rich mythological tradition and stands as a reminder of what all were lost and found in the passage of time.

Priam’s Treasure – Turkey

Image Credit: The Mask of Homer’s Agamemnon in National Archaeological Museum of Athens

Priam’s treasure is a dazzling collection of ancient gold jewellery, tolls and artifacts collected from the legendary city of Troy. Discovered in 1873 by the German adventurer Heinrich Schliemann, in modern-day Turkey, the sensational treasure was believed to be the ruins of Homer’s Troy.

Smuggled out of the Ottoman Empire and gifted to Berlin, it dazzled Europe with its shimmering necklaces, earrings and ceremonial relics. As World War II ravaged the city, museum staff hid the treasure in bunkers, before it was seized by the advancing Soviet troops in 1945. For five decades it was locked away in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. The mystery was revealed in 1990’s, igniting international disputes over rightful ownership and wartime ruins.

While Germany continues to lobby for its return, Russia’s post-war laws claim its reparation. They are currently at the Pushkin Museum, standing as a symbol of ancient myth, 19th century ambition and 20th century conflicts.