By Team ACF

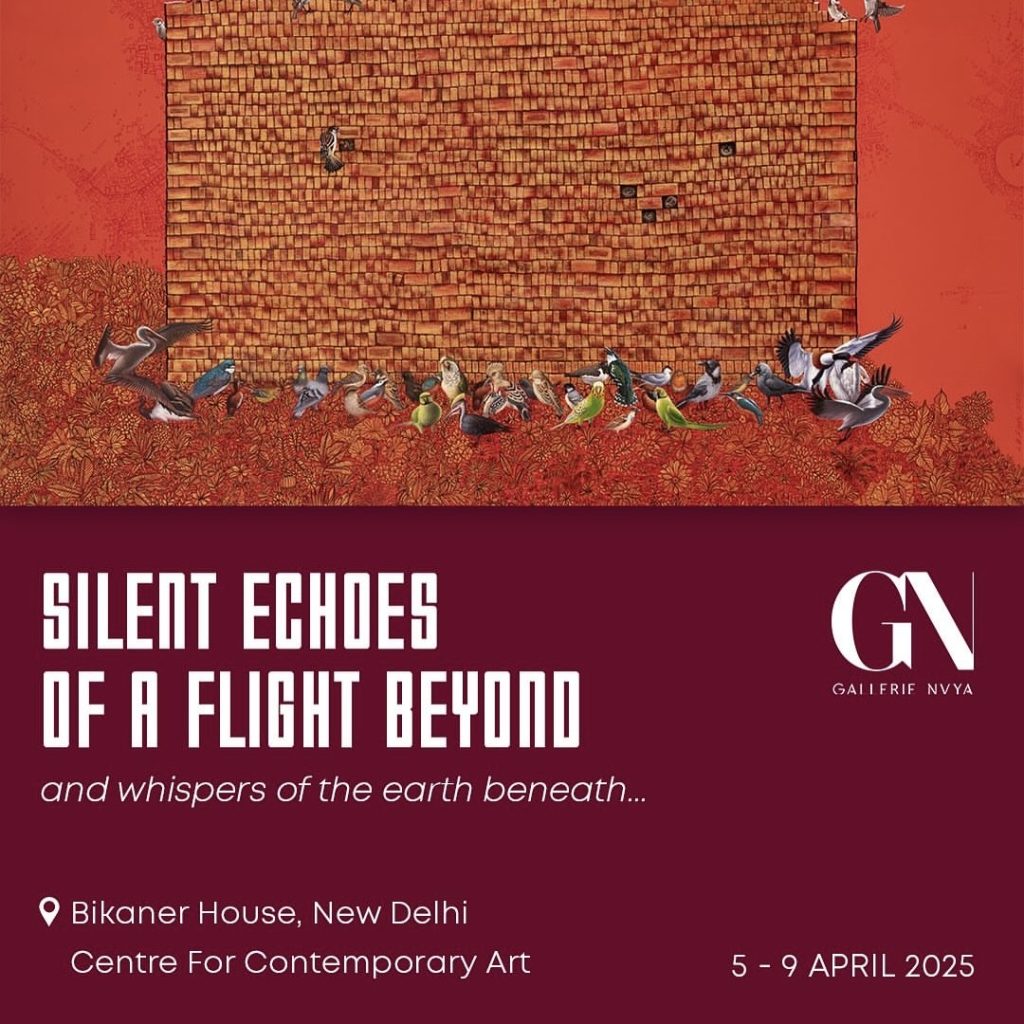

“Shakti: Fair & Fierce exhibition represents different narratives and diverse perspectives as it celebrates feminine creativity and empowerment.” – Sushma Bahl, Art Advisor, Curator and Writer

In a world where the feminine is too often confined, silenced, or simplified, curator and author Sushma Bahl brings forth a powerful counterpoint through the Shakti: Fair & Fierce exhibition. Showcasing over 100 works by 55 women artists, the exhibition charts a bold trajectory—from myth to modernity, thread to technology, body to cosmos. In this conversation, Sushma Bahl reflects on the artistic voices that challenge patriarchy, reclaim space, and thread together the fair and the fierce in the evolving story of feminine strength.

Sushma Bahl, Art Advisor, Curator and Writer

- The exhibition is segmented into Voice & Vision, Myth & Mystique, and Liberating Threads. Could you walk us through how these themes evolved and what they aim to reveal about feminine creativity and empowerment?

The work was so varied in style. There were artists like Madhvi Parekh, Jayasri Burman, and Seema Kohli who are so well known, and there were totally unknown artists. There were young people from Baroda who were just out of college, and there were these rural women, women from Kashmir who were doing embroidery work, and so on. There were sculptures, and new media works, it was so varied—how were we going to put it all together so that it makes sense?

So, I thought the best way we could do it is to link them thematically, story-wise, or by what each picture had to say, because each is seen and shown in different ways. But I think when you look at it, what is the main thrust of each work? Keeping that in mind, I divided the exhibition into these three sections.

One is Voice and Vision, which is—you know—women expressing their voice through their art. They are expressing their vision, their dreams, their fears, their anxiety, and their life through their work. Then we had this section, Myth and Mystique, in India, a lot of women, particularly in rural India, but even in urban India, like Jayshree Burman’s work, it’s all based on mythology. And similarly, other artists—even very contemporary ones like Charuvi—her work is about Kundalini. It’s all inspired by mythology. There is one work that talks about the Chirharan in Mahabharata, and another of Ardhnarishwar—we wanted to show in this section what the mythology and myth are. The third section, Threading Life, not only includes thread work, but also works that connect life to other kinds of events and their feelings and emotions. So putting all these together in three sections gave us a good, solid shape.

- The exhibition beautifully blends mythology with contemporary narratives. How do you see the role of myth in shaping or challenging present-day notions of Naari Shakti?

As the title Shakti: Fair and Fierce suggests, it’s about women, because in our belief system, Shakti is considered a powerful female deity. So, the exhibition takes off from that idea. You know, we also used to have this whitening cream—because in India, if girls are not “fair,” they are not considered beautiful. But here, fair is not about colour; it’s about fairness in attitude, in their way of life, and in what they do. And fierce—because when women are mistreated, they can become Kali, Durga, or any other powerful form you like.

What we find in Indian mythology, spirit, and thinking is that women are treated as truly great mother figures. Even in Ajanta, Ellora, and going back to the Indus Valley Civilization, the woman figure has been revered through the centuries. But at the same time, she has also been exploited, marginalized, and sexually mistreated—in multiple ways.

So, the idea was to show through art that women today are seeking equity. They are demanding and asserting their right to be women in their own right. There was a time when women were seen only as housewives and mothers—the nurturing, giving mother. But now, she can also be someone who asks for something, who demands independence. She is a multitasker. What’s amazing is that Indian women today are handling their homes, but also doing equally well in the outside world.

The best example I can quote is the two female army officers who represented the Indian armed forces. It was so inspiring—it gave you a sense of pride. And that’s what this exhibition is about: showing pride through art.

Now, when you plan an exhibition, you have to give it a shape—some people do it year-wise, genre-wise, colour-wise, theme-wise. In our case, we had the theme. We commissioned artists, and all the works were selected and acquired for the Museum of Sacred Art in Belgium. So, everyone who participated in this project has earned something—it gave them economic independence. Fifty-five women, a hundred works—and the idea was to talk about women across age, caste, creed, region; junior, senior; high art, low art; art and craft.

Of course, we couldn’t have an endless brief. So the one decision we made was that all artists had to be living artists—people working today. Like, you know, Amrita Sher-Gil is the biggest inspiration, but she is no longer with us. So everyone in this exhibition is someone who is living somewhere in India today and making some or the other kind of art—and benefiting from it.

Ancient Indian art is appreciated and even collected. But modern Indian art—especially by women—hasn’t been exhibited as much as that by men. Women get marginalized, even by gallerists. So the idea was to give them space, and to show the work at NGMA, in Delhi and Bombay, and now in Belgium—to give them that platform. It’s just wonderful.

3. Many works in Shakti: Fair & Fierce engage with newer media like digital art and video alongside traditional forms. What does this interdisciplinary mix say about how women artists are redefining creative boundaries today?

When I was researching in Kutch, I met a woman—now a mother of three—whose community used to insist on making elaborate mirror-work ghagharas (skirts) as a marriage prerequisite: “Until you make this perfectly, you won’t marry,” they’d say. Girls who couldn’t complete the intricate embroidery simply couldn’t wed, and families grew anxious.

Later on the elders finally said, “This tradition isn’t serving anyone—let’s stop it.” That’s when this woman began stitching small pouches and bags instead. Today, she runs her own website, sells internationally, and even her husband, who ran a tiny grocery stall, has given up his shop and helps her in her art. Watching her say, “Now you do this, and you do that,” and seeing the confidence in her voice—that is real Naari Shakti: women coming into their own.

If you look at traditional Indian miniature paintings, women have always mixed and applied the pigments, yet in the marketplace, it was men who received credit and profit. This exhibition gave these artists a platform to say, “This is my work; this is our work.” I’ll never forget the moment a Kashmiri embroiderer-who had never before left her valley-stood proudly beside her piece, spoke to the minister, and declared, “This is mine.”

4. What conversations or reflections do you hope this exhibition sparks—both within the art world and among wider audiences—about the role and representation of women in contemporary creative practice?

A certain percentage of women in the political space means they can now enter policy-making, and policy also relates to culture and art. I think this exhibition has become a talking point, and the fact that it traveled and was seen by so many people means there’s a ripple effect. I won’t say things change overnight—they don’t. You know how many years we’ve been fighting for our rights, all over the world.

What I want to emphasise is that the marginalisation of women isn’t just an Indian issue—it’s global. The MeToo movement started elsewhere, and look at what’s happening in Iran, Afghanistan, and even China. I remember when I went to Korea for the first time, I was there as my husband’s wife—he’s a scientist—and I got invited to a few dinners, but I hardly saw any women in those circles. The next time I went, I was invited as a speaker for a cultural conference. That time, there were men and women, more interaction, but even then, when I spoke with people, they said women are still expected to take care of the home before being “allowed” to step out.

So it’s a global condition. In India, we are very double-faced. On one side, we call her mata, devi—and on the other, we beat her up. This contradiction is something we hope the exhibition provokes people to reflect on.

Through Shakti: Fair & Fierce, I hope audiences—both within the art world and outside of it—begin to question these imbalances and start conversations about representation, respect, and real empowerment. It’s about showing women as full individuals—creative, strong, and deserving of space—not just in art, but in every sphere of life.

5. As a woman curator with an extensive body of work, how has your own journey shaped the way you approach projects like Shakti: Fair & Fierce?

There has to be a story you want to tell—why are you doing it? Is it just because there’s an assignment, or is there a real purpose behind it? If there’s no purpose, then it feels very hollow. So whatever story you decide on, you have to present it in a way the audience can connect with. You need to consider: who is your audience? What is their level of understanding or interest? If it’s a large, diverse audience with varied backgrounds, then you must plan your project in a way that resonates with all of them. When I worked at the British Council, things were very different—I had the liberty to do things in my own way. But when you’re working as a freelancer, there are often constraints from the sponsoring agency—they may have certain expectations or demands, and you have to factor those in. So, quite often, there’s a struggle between maintaining the integrity of your vision and meeting the commercial needs. At times, you have to make compromises. But as a curator, you must ensure that those compromises do not diminish the core significance of the project.

I think whatever I’ve done over the years—like when I worked on a project at the British Museum, V&A—I’ve learnt a lot. I learnt about display, about lighting, about captioning—all these things are important, and we are now beginning to give them more attention. But earlier, works were just put up in museums without much thought. So all these aspects—how works are displayed—are important, and I feel I’ve been able to add that to my curatorial work.

Also, I like to make whatever project I do—depending on the resources available—as inclusive as possible. Because when I’m talking to artists, some senior ones ask, “Whose works are you including?” I say, “Don’t ask me that—I’ll take young artists as well as senior ones.” They want to know, “Is this work at our level or not?” It doesn’t matter whose level it is. Seniors gain from working with young people, and young people gain from working with seniors. So I think there is a give and take, which people really love.

When you are displaying work, you have a vision. Whether a piece goes under Voice and Vision or Myth and Mystique—that’s something I have to decide. Some artists might feel, “My work could have gone in the other section too.” Yes, it could have—but this is what the curator envisioned. Sometimes, you have to use your own authority, your judgment—whatever you like to call it—to decide. So I think these are the things I’ve learnt and added to the projects over time.

Seema Kohli – Tree of Life

6. What advice would you offer to young women curators who are just beginning their journey—especially those looking to amplify underrepresented voices through art?

I think, first of all, you need to feel committed to what you want to do, and you have to be ready to take risks. When you want to play it safe, you don’t go very far, because you’ll only stay within your comfort zone. But when you’re willing to take risks—okay, out of ten things, some will fail and some will work—then next time you know what worked, what didn’t, and why. That’s how you improve.

So I would say to young people: be prepared to take risks, be bold, and put in your best. Don’t cut corners. Don’t think about how much money something will fetch you, or whose work will or won’t be seen—these things should not influence you when you’re curating or creating art.

For example, many artists are asked to keep making similar things because they sell. Sometimes, you have to put that aside and say, “No, I would prefer to do something that gives me satisfaction.” Unless the artist himself or herself is happy, the audience won’t be happy either.

Kanchan Chander – Double Collage Torso with Krishna and Kali

Shakti: Fair & Fierce is more than an exhibition—it’s a dynamic narrative of feminine strength, storytelling, and resilience. Curated with thoughtful intention by Sushma Bahl, it brings together over 55 women artists across generations, geographies, and genres. From mythology to modernity, embroidery to digital media, it celebrates women asserting their agency, challenging norms, and reclaiming space through their creative voices. With its thematic coherence and inclusive spirit, the exhibition becomes a powerful platform for dialogue, pride, and transformation—both within the art world and beyond.

After showing at NGMA Delhi and Mumbai, it is now on view at the Museum of Sacred Art (MOSA), Belgium. The opening on May 24 at Domaine de Radhadesh includes music, dance, and talks that honor the dynamic spirit of women in art.

Arpana Caur – Day and Night